What Time Is Service South West Church

| Cathedral of the Intercession of Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat | |

|---|---|

| Собор Покрова Пресвятой Богородицы, что на Рву (Russian) | |

Saint Basil's Cathedral as viewed from Red Foursquare | |

| Faith | |

| Affiliation | Russian Orthodox |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | State Historical Museum with occasional church services since 1991 |

| Year consecrated | 12 July 1561 (1561-07-12) [1] |

| Condition | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Red Square, Moscow, Russia |

| Geographic coordinates | 55°45′9″N 37°37′23″East / 55.75250°N 37.62306°E / 55.75250; 37.62306 Coordinates: 55°45′9″Northward 37°37′23″Due east / 55.75250°North 37.62306°E / 55.75250; 37.62306 |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Ivan Barma and Postnik Yakovlev[2] |

| Type | Church |

| Groundbreaking | 1555 (1555) |

| Specifications | |

| Pinnacle (max) | 47.5 metres (156 ft)[3] |

| Dome(s) | 10 |

| Dome elevation (inner) | ff |

| Spire(s) | ii |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official proper name: Kremlin and Red Square, Moscow | |

| Blazon | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, four, vi |

| Designated | 1990[4] |

| Reference no. | 545 |

| State Party | Russia |

| Region | Europe |

| Session | 14th |

| Website | |

| Cathedral of Vasily the Blessed [ expressionless link ] State Historical Museum | |

The Cathedral of Vasily the Blessed (Russian: Собо́р Васи́лия Блаже́нного , tr. Sobór Vasíliya Blazhénnogo ), commonly known as Saint Basil'southward Cathedral, is an Orthodox church in Red Square of Moscow, and is one of the almost popular cultural symbols of Russia. The building, now a museum, is officially known as the Cathedral of the Intercession of the Almost Holy Theotokos on the Moat, or Pokrovsky Cathedral.[5] Information technology was built from 1555 to 1561 on orders from Ivan the Terrible and commemorates the capture of Kazan and Astrakhan. Information technology was the metropolis's tallest building until the completion of the Ivan the Nifty Bell Tower in 1600.[vi]

The original building, known as Trinity Church and after Trinity Cathedral, contained eight chapels bundled effectually a ninth, central chapel dedicated to the Intercession; a tenth chapel was erected in 1588 over the grave of the venerated local saint Vasily (Basil). In the 16th and 17th centuries, the church, perceived (as with all churches in Byzantine Christianity) as the earthly symbol of the Heavenly Metropolis,[7] was popularly known every bit the "Jerusalem" and served equally an allegory of the Jerusalem Temple in the annual Palm Sun parade attended by the Patriarch of Moscow and the Tsar.[8]

The cathedral has nine domes (each one respective to a different church) and is shaped like the flame of a bonfire ascent into the heaven.[ix] Dmitry Shvidkovsky, in his volume Russian Architecture and the Westward, states that "it is like no other Russian building. Zilch like can be found in the entire millennium of Byzantine tradition from the fifth to the fifteenth century ... a strangeness that astonishes past its unexpectedness, complexity and dazzling interleaving of the manifold details of its design."[10] The cathedral foreshadowed the climax of Russian national compages in the 17th century.[11]

As part of the program of state atheism, the church was confiscated from the Russian Orthodox community as part of the Soviet Union's antireligious campaigns and has operated as a division of the State Historical Museum since 1928.[12] Information technology was completely secularized in 1929,[12] and remains a federal property of the Russian Federation. The church building has been role of the Moscow Kremlin and Carmine Foursquare UNESCO Earth Heritage Site since 1990.[thirteen] [14] With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, weekly Orthodox Christian services with prayer to St. Basil accept been restored since 1997.[15]

Construction under Ivan IV [edit]

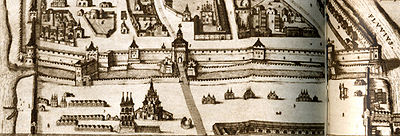

Red Square, early 17th-century. Fragment from Blaeu Atlas. The construction with iii roof tents in the foreground left is the originally detached belfry of the Trinity Church, non drawn to scale. Trinity Church stands behind it, slightly closer to the road starting at St. Frol's (later on Saviour'south ) Gate of the Kremlin. The horseshoe-shaped object near the road in the foreground is Lobnoye Mesto.

The site of the church had been, historically, a decorated market between the St. Fool'south (later Saviour's) Gate of the Moscow Kremlin and the outlying posad. The center of the market place was marked by the Trinity Church building, built of the aforementioned white stone as the Kremlin of Dmitry Donskoy (1366–68) and its cathedrals. Tsar Ivan IV marked every victory of the Russo-Kazan War by erecting a wooden memorial church next to the walls of Trinity Church; by the stop of his Astrakhan entrada, it was shrouded inside a cluster of seven wooden churches. According to the study in Nikon's Chronicle, in the autumn of 1554 Ivan ordered the structure of the wooden Church of Intercession on the same site, "on the moat".[16] I year after, Ivan ordered the construction of a new stone cathedral on the site of Trinity Church to commemorate his campaigns. Dedication of a church to a war machine victory was "a major innovation"[10] for Muscovy. The placement of the church exterior the Kremlin walls was a political statement in favor of posad commoners and confronting hereditary boyars.[17]

Contemporary commentators clearly identified the new building every bit Trinity Church building, later its easternmost sanctuary;[16] the status of "katholikon" ( собор , sobor , large assembly church) had not been bestowed on it however:

On the Trinity on the Moat in Moscow.

In the same yr, through the volition of czar and lord and one thousand prince Ivan began making the pledged church building, as he promised for the capture of Kazan: Trinity and Intercession and 7 sanctuaries, also chosen "on the moat". And the architect was Barma with company.

The identity of the architect is unknown.[nineteen] Tradition held that the church was built by two architects, Barma and Postnik:[19] [20] the official Russian cultural heritage register lists "Barma and Postnik Yakovlev".[2] Researchers proposed that both names refer to the same person, Postnik Yakovlev[20] or, alternatively, Ivan Yakovlevich Barma (Varfolomey).[xix] Legend held that Ivan blinded the builder and so that he could not re-create the masterpiece elsewhere.[21] [22] [23] Many historians are convinced that it is a myth, as the architect afterward participated in the construction of the Cathedral of the Annunciation in Moscow as well as in building the walls and towers of the Kazan Kremlin.[24] [25] Postnik Yakovlev remained active at least throughout the 1560s.[26]

At that place is prove that construction involved stonemasons from Pskov[27] and German lands.[28]

Architectural style [edit]

Ascension Church building in Kolomenskoye (far left), a probable influence on the cathedral,[29] and the Dyakovo church (eye)[30]

Because the church building has no analog—in the preceding, contemporary, or later architecture of Muscovy and Byzantine cultural tradition, in full general,[10]—the sources that inspired Barma and Postnik are disputed. Eugène Viollet-le-Duc rejected European roots for the cathedral, opining that its corbel arches were Byzantine and ultimately Asian.[31] A modern "Asian" hypothesis considers the cathedral a recreation of Qolşärif Mosque, which was destroyed by Russian troops after the Siege of Kazan.[32]

Nineteenth-century Russian writers, starting with Ivan Zabelin,[7] emphasized the influence of the colloquial wooden churches of the Russian N; their motifs made their ways into masonry, particularly the votive churches that did not need to firm substantial congregations.[33] David Watkin likewise wrote of a blend of Russian and Byzantine roots, calling the cathedral "the climax" of Russian vernacular wooden architecture.[34]

The church combines the staggered layered design of the primeval (1505–1508) office of the Ivan the Great Bell Belfry,[35] the central tent of the Church building of Ascension in Kolomenskoye (1530s), and the cylindric shape of the Church of Beheading of John the Baptist in Dyakovo (1547);[29] just the origin of these unique buildings is equally debated. The Church building in Kolomenskoye, according to Sergei Podyapolsky, was built by Italian Petrok Maly,[28] although mainstream history has not yet accustomed his opinion. Andrey Batalov revised the year of completion of Dyakovo church from 1547 to the 1560s–70s, and noted that Trinity Church could have had no tangible predecessors at all.[36]

Forepart elevation cartoon of the cathedral'southward façade and overhead view of floor programme

Dmitry Shvidkovsky suggested that the "improbable" shapes of the Intercession Church and the Church of Rise in Kolomenskoye manifested an emerging national renaissance, blending earlier Muscovite elements with the influence of Italian Renaissance.[37] A large group of Italian architects and craftsmen continuously worked in Moscow in 1474–1539, as well equally Greek refugees who arrived in the city after the autumn of Constantinople.[38] These ii groups, co-ordinate to Shvidkovsky, helped Moscow rulers in forging the doctrine of Third Rome, which in turn promoted assimilation of gimmicky Greek and Italian culture.[38] Shvidkovsky noted the resemblance of the cathedral's floorplan to Italian concepts by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Donato Bramante, only near likely Filarete's Trattato di architettura. Other Russian researchers noted a resemblance to sketches by Leonardo da Vinci, although he could not accept been known in Ivan's Moscow.[39] Nikolay Brunov recognized the influence of these prototypes but not their significance;[twoscore] he suggested that mid-16th century Moscow already had local architects trained in Italian tradition, architectural drawing and perspective, and that this civilisation was lost during the Fourth dimension of Troubles.[41]

Crowd on the Red Square in front of the St. Basil Cathedral

Andrey Batalov wrote that judging by the number of novel elements introduced with Trinity Church, information technology was most likely built past German craftsmen.[28] Batalov and Shvidkovsky noted that during Ivan'due south reign, Germans and Englishmen replaced Italians, although German influence peaked later during the reign of Mikhail Romanov.[28] German influence is indirectly supported by the rusticated pilasters of the key church building, a characteristic more mutual in contemporary Northern Europe than in Italian republic.[42]

The 1983 academic edition of Monuments of Compages in Moscow takes the center ground: the church is, most likely, a production of the complex interaction of singled-out Russian traditions of wooden and stone architecture, with some elements borrowed from the works of Italians in Moscow.[43] Specifically, the fashion of brickwork in the vaults is Italian.[43]

Layout [edit]

Instead of following the original advertizing hoc layout (vii churches around the fundamental core), Ivan's architects opted for a more symmetrical flooring programme with viii side churches around the core,[20] producing "a thoroughly coherent, logical plan"[44] [45] despite the erroneous latter "notion of a structure devoid of restraint or reason"[44] influenced by the retentiveness of Ivan'southward irrational atrocities.[44] The fundamental cadre and the 4 larger churches placed on the four major compass points are octagonal; the four diagonally placed smaller churches are cuboid, although their shape is hardly visible through later additions.[46] The larger churches stand on massive foundations, while the smaller ones were each placed on a raised platform equally if hovering higher up ground.[47]

Although the side churches are arranged in perfect symmetry, the cathedral as a whole is not.[48] [49] The larger central church building was deliberately[48] offset to the west from the geometric eye of the side churches, to arrange its larger apse[48] on the eastern side. As a result of this subtle calculated[48] asymmetry, viewing from the north and the south presents a circuitous multi-axial shape, while the western facade, facing the Kremlin, appears properly symmetrical and monolithic.[48] [49] The latter perception is reinforced by the fortress-fashion machicolation and corbeled cornice of the western Church building of Entry into Jerusalem, mirroring the existent fortifications of the Kremlin.[50]

Inside the composite church is a labyrinth of narrow vaulted corridors and vertical cylinders of the churches.[29] Today the cathedral consists of ix individual chapels.[51] The largest, central one, the Church building of the Intercession, is 46 metres (151 ft) tall internally but has a floor area of only 64 foursquare metres (690 sq ft).[29] Even so, it is wider and airier than the church in Kolomenskoye with its uncommonly thick walls.[52] The corridors functioned every bit internal parvises; the western corridor, adorned with a unique flat caissoned ceiling, doubled every bit the narthex.[29]

The detached belfry of the original Trinity Church stood southwest or south of the main structure. Tardily 16th- and early 17th-century plans describe a simple structure with three roof tents, most likely covered with canvass metal.[53] No buildings of this type survive to engagement, although it was then common and used in all of the pass-through towers of Skorodom.[54] August von Meyenberg's panorama (1661) presents a different building, with a cluster of small-scale onion domes.[53]

Structure [edit]

The pocket-sized dome on the left marks the sanctuary of Basil the Blessed (1588).

The foundations, equally was traditional in medieval Moscow, were built of white stone, while the churches themselves were built of carmine brick (28 by 14 by viii cm (11.0 by 5.5 past three.i in)), so a relatively new material[20] (the kickoff attested brick building in Moscow, the new Kremlin Wall, was started in 1485).[55] Surveys of the structure show that the basement level is perfectly aligned, indicating use of professional drawing and measurement, merely each subsequent level becomes less and less regular.[56] Restorers who replaced parts of the brickwork in 1954–1955 discovered that the massive brick walls conceal an internal wooden frame running the entire meridian of the church.[7] [57] This frame, made of elaborately tied thin studs, was erected as a life-size spatial model of the time to come cathedral and was then gradually enclosed in solid masonry.[7] [57]

The builders, fascinated by the flexibility of the new technology,[58] used brick every bit a decorative medium both inside and out, leaving every bit much brickwork open as possible; when location required the apply of rock walls, information technology was busy with a brickwork pattern painted over stucco.[58] A major novelty introduced by the church building was the employ of strictly "architectural" ways of exterior decoration.[59] Sculpture and sacred symbols employed by earlier Russian compages are completely missing; floral ornaments are a subsequently addition.[59] Instead, the church boasts a multifariousness of three-dimensional architectural elements executed in brick.

Color [edit]

The church building acquired its present-solar day bright colors in several stages from the 1680s[seven] to 1848.[43] Russian attitude towards color in the 17th century changed in favor of brilliant colors; iconographic and mural art experienced an explosive growth in the number of available paints, dyes and their combinations.[60] The original colour scheme, missing these innovations, was far less challenging. It followed the depiction of the Heavenly Urban center in the Book of Revelation:[61]

And he that sat was to expect upon like a jasper and a sardine rock: and in that location was a rainbow round near the throne, in sight like unto an emerald.

And round about the throne were four and twenty seats: and upon the seats, I saw 4 and twenty elders sitting, clothed in white raiment; and they had on their heads crowns of gold.

Color scheme of the cathedral seen by night.

The 25 seats from the biblical reference are alluded to in the building's construction, with the addition of eight pocket-sized onion domes around the central tent, four around the western side church and four elsewhere. This organisation survived through about of the 17th century.[62] The walls of the church mixed blank red brickwork or painted imitation of bricks with white ornaments, in roughly equal proportion.[61] The domes, covered with tin, were uniformly gilded, creating an overall bright but fairly traditional combination of white, red and aureate colors.[61] Moderate use of light-green and blue ceramic inserts provided a touch on of rainbow equally prescribed past the Bible.[61]

While historians agree on the colour of the 16th-century domes, their shape is disputed. Boris Eding wrote that they nearly likely were of the same onion shape as the present-day domes.[63] However, both Kolomenskoye and Dyakovo churches have flattened hemispherical domes, and the same blazon could have been used by Barma and Postnik.[64]

Development [edit]

1583–1596 [edit]

The original Trinity Church burnt downward in 1583 and was refitted by 1593.[43] The ninth sanctuary, defended to Basil Fool for Christ (the 1460s–1552), was added in 1588 side by side to the northward-eastern sanctuary of the 3 Patriarchs.[43] Another local fool, Ivan the Blessed, was buried on the church grounds in 1589; a sanctuary in his memory was established in 1672 inside the due south-eastern arcade.[7]

The vault of the Saint Basil Sanctuary serves as a reference bespeak in evaluating the quality of Muscovite stonemasonry and applied science. As 1 of the first vaults of its blazon, it represents the average of engineering science craft that peaked a decade later in the church of the Trinity in Khoroshovo (completed 1596).[65] The craft was lost in the Time of Troubles; buildings from the offset one-half of the 17th century lack the refinement of the belatedly 16th century, compensating for poor construction skill with thicker walls and heavier vaults.[65]

1680–1683 [edit]

The second, and most pregnant, circular of refitting and expansion took place in 1680–1683.[7] The nine churches themselves retained their advent, just additions to the ground-flooring arcade and the offset-flooring platform were so profound that Nikolay Brunov rebuilt a composite church building from an "old" building and an contained piece of work that incorporated the "new" Trinity Church.[66] What one time was a group of ix independent churches on a mutual platform became a monolithic temple.[66] [67]

The formerly open ground-floor arcades were filled with brick walls; the new space housed altars from 13 quondam wooden churches erected on the site of Ivan's executions in Ruby-red Square.[7] Wooden shelters above the commencement-floor platform and stairs (the cause of frequent fires) were rebuilt in brick, creating the present-mean solar day wrap-around galleries with tented roofs to a higher place the porches and vestibules.[seven]

The sometime detached belfry was demolished; its foursquare basement was reused for a new belltower.[7] The alpine unmarried tented roof of this belltower, built in the vernacular fashion of the reign of Alexis I, significantly changed the appearance of the cathedral, adding a strong asymmetrical counterweight to the church itself.[68] The effect is about pronounced on the southern and eastern facades (equally viewed from Zaryadye), although the belltower is big plenty to be seen from the west.[68]

The first ornamental murals in the cathedral appeared in the same period, starting with floral ornaments within the new galleries; the towers retained their original brickwork pattern.[7] Finally, in 1683, the church building was adorned with a tiled cornice in yellow and blue, featuring a written history of the church building[7] in One-time Slavic typeface.

1737–1784 [edit]

In 1737 the church building was damaged past a massive fire and later restored past Ivan Michurin.[69] The inscriptions made in 1683 were removed during the repairs of 1761–1784. The church building received its commencement figurative murals inside the churches; all exterior and interior walls of the offset ii floors were covered with floral ornamentation.[7] The belltower was connected with the church through a footing-floor annex;[7] the last remaining open arches of the sometime ground-floor arcade were filled during the same menstruum,[7] erasing the last hint of what was once an open platform carrying the nine churches of Ivan's Jerusalem.

1800–1848 [edit]

Paintings of Reddish Foursquare by Fyodor Alekseyev, made in 1800–1802, show that by this time the church was enclosed in an apparently chaotic cluster of commercial buildings; rows of shops "transformed Reddish Foursquare into an oblong and airtight yard."[70] In 1800 the space between the Kremlin wall and the church was even so occupied by a moat that predated the church building itself.[71] The moat was filled in grooming for the coronation of Alexander I in 1801.[72] The French troops who occupied Moscow in 1812 used the church building for stables and looted anything worth taking.[69] The church was spared past the Fire of Moscow (1812) that razed Kitai-gorod, and by the troops' failure to blow it up according to Napoleon's order.[69] The interiors were repaired in 1813 and the exterior in 1816. Instead of replacing missing ceramic tiles of the chief tent, the Church building preferred to merely cover information technology with a can roof.[73]

The fate of the immediate environment of the church building has been a bailiwick of dispute between city planners since 1813.[74] Scotsman William Hastie proposed clearing the space around all sides of the church and all the way down to the Moskva River;[75] the official commission led by Fyodor Rostopchin and Mikhail Tsitsianov[76] agreed to articulate just the space between the church building and Lobnoye Mesto.[75] Hastie's plan could accept radically transformed the city,[74] but he lost to the opposition, whose plans were finally endorsed by Alexander I in December 1817[75] (the specific determination on immigration the rubble around the church was issued in 1816).[69]

Nevertheless, bodily redevelopment by Joseph Bove resulted in clearing the rubble and creating Vasilyevskaya (St. Basil's) Foursquare between the church and Kremlin wall by shaving off the crest of the Kremlin Hill between the church and the Moskva River.[77] Cerise Square was opened to the river, and "St. Basil thus crowned the decapitated hillock."[77] Bove built the stone terrace wall separating the church from the pavement of Moskvoretskaya Street; the southern side of the terrace was completed in 1834.[seven] Modest repairs continued until 1848, when the domes acquired their nowadays-day colours.[43]

1890–1914 [edit]

Postcard, early 20th century

Preservationist societies monitored the land of the church and called for a proper restoration throughout the 1880s and 1890s,[78] [79] but it was regularly delayed for lack of funds. The church did not have a congregation of its ain and could only rely on donations raised through public campaigning;[80] national authorities in Saint petersburg and local in Moscow prevented financing from state and municipal budgets.[80] In 1899 Nicholas II reluctantly admitted that this expense was necessary,[81] simply once again all the involved country and municipal offices, including the Holy Synod, denied financing.[81] Restoration, headed by Andrey Pavlinov (died 1898) and Sergey Solovyov, dragged on from 1896[82] to 1909; in full, preservationists managed to raise effectually 100,000 roubles.[81]

Restoration began with replacing the covering of the domes.[79] Solovyov removed the tin roofing of the main tent installed in the 1810s and found many original tiles missing and others discoloured;[79] after a protracted fence the whole set of tiles on the tented roof was replaced with new ones.[79] Some other dubious decision allowed the use of standard bricks that were smaller than the original 16th-century ones.[83] Restorers agreed that the paintwork of the 19th century must exist replaced with a "true recreation" of historic patterns, but these had to be reconstructed and deduced based on medieval miniatures.[84] In the end, Solovyov and his advisers chose a combination of deep red with deep green that is retained to the present.[84]

Saint Basil's Cathedral in 1910

In 1908 the church received its first warm air heating organisation, which did not work well because of heat losses in long air ducts, heating simply the eastern and northern sanctuaries.[85] In 1913 it was complemented with a pumped water heating system serving the residuum of the church building.[85]

1918–1941 [edit]

During Earth State of war I, the church building was headed by protoiereus Ioann Vostorgov, a nationalist preacher and a leader of the Blackness-Hundredist Spousal relationship of the Russian People. Vostorgov was arrested past Bolsheviks in 1918 on a pretext of embezzling nationalized church backdrop and was executed in 1919.[ commendation needed ] The church briefly enjoyed Vladimir Lenin's "personal interest";[86] in 1923 it became a public museum, though religious services continued until 1929.[12]

Bolshevik planners entertained ideas of demolishing the church afterwards Lenin'due south funeral (January 1924).[87] In the showtime half of the 1930s, the church became an obstacle for Joseph Stalin's urbanist plans, carried out by Moscow party boss Lazar Kaganovich, "the moving spirit behind the reconstruction of the capital".[88] The disharmonize between preservationists, notably Pyotr Baranovsky, and the assistants continued at to the lowest degree until 1936 and spawned urban legends. In particular, a frequently-told story is that Kaganovich picked upwards a model of the church building in the process of envisioning Cherry Square without it, and Stalin sharply responded "Lazar, put information technology back!" Similarly, Stalin'south main planner, builder Vladimir Semyonov, reputedly dared to "grab Stalin'due south elbow when the leader picked up a model of the church to see how Ruby-red Square would await without it" and was replaced by pure functionary Sergey Chernyshov.[89]

In the autumn of 1933, the church building was struck from the heritage register. Baranovsky was summoned to perform a concluding-minute survey of the church slated for sabotage, and was then arrested for his objections.[90] While he served his term in the Gulag, attitudes inverse and past 1937 even hard-line Bolshevik planners admitted that the church should be spared.[91] [92] In the spring of 1939, the church was locked, probably because sabotage was again on the calendar;[93] however, the 1941 publication of Dmitry Sukhov's detailed book[94] on the survey of the church in 1939–1940 speaks against this supposition.

1947 to nowadays [edit]

In the start years after Earth War Ii renovators restored the historical ground-floor arcades and pillars that supported the start-floor platform, cleared upward vaulted and caissoned ceilings in the galleries, and removed "unhistoric" 19th-century oil pigment murals within the churches.[7] Another round of repairs, led past Nikolay Sobolev in 1954–1955, restored original paint imitating brickwork, and allowed restorers to dig inside one-time masonry, revealing the wooden frame inside it.[vii] In the 1960s, the tin can roofing of the domes was replaced with copper.[12]

The last round of renovation was completed in September 2008 with the opening of the restored sanctuary of St. Alexander Svirsky.[95] The edifice is still partly in employ today as a museum and, since 1991, is occasionally used for services by the Russian Orthodox Church building. Since 1997 Orthodox Christian services take been held regularly. Nowadays every Lord's day at Saint Basil'south church there is a divine liturgy at 10AM with an akathist to Saint Basil.[96] [15]

Naming [edit]

The building, originally known every bit "Trinity Church",[x] was consecrated on 12 July 1561,[12] and was subsequently elevated to the condition of a sobor (similar to an ecclesiastical basilica in the Catholic Church, but usually and incorrectly translated as "cathedral").[97] "Trinity", co-ordinate to tradition, refers to the easternmost sanctuary of the Holy Trinity, while the central sanctuary of the church is dedicated to the Intercession of Mary. Together with the westernmost sanctuary of the Entry into Jerusalem, these sanctuaries form the main eastward–west axis (Christ, Mary, Holy Trinity), while other sanctuaries are dedicated to individual saints.[98]

| Compass point[99] | Type[99] | Dedicated to[99] | Commemorates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key core | Tented church building | Intercession of Most Holy Theotokos | Beginning of the final assault of Kazan, 1 October 1552 |

| West | Column | Entry of Christ into Jerusalem | Triumph of the Muscovite troops |

| North-west | Groin vault | Saint Gregory the Illuminator of Armenia | Capture of Ars Belfry of Kazan Kremlin, thirty September 1552 |

| North | Column | Saint Martyrs Cyprian and Justinia (since 1786 Saint Adrian and Natalia of Nicomedia) | Complete capture of Kazan Kremlin, 2 Oct 1552 |

| North-east | Groin vault | 3 Patriarchs of Alexandria (since 1680 Saint John the Merciful) | Defeat of Yepancha's cavalry on 30 Baronial 1552 |

| E | Cavalcade | Life-giving Holy Trinity | Historical Trinity Church on the same site |

| South-east | Groin vault | Saint Alexander Svirsky | Defeat of Yepancha's cavalry on 30 August 1552 |

| South | Cavalcade | The icon of Saint Nicholas from the Velikaya River (Nikola Velikoretsky) | The icon was brought to Moscow in 1555. |

| Southward-due west | Groin vault | Saint Barlaam of Khutyn | May accept been built to commemorate Vasili Three of Russia[100] |

| North-eastern annex (1588) | Groin vault | Basil the Blessed | Grave of venerated local saint |

| South-eastern annex (1672) | Groin vault | Laying the Veil (since 1680: Nativity of Theotokos, since 1916: Saint John the Blest of Moscow) | Grave of venerated local saint |

The name "Intercession Church" came into apply later,[10] coexisting with Trinity Church. From the end of the 16th century[67] to the cease of the 17th century the cathedral was besides popularly called Jerusalem, with reference to its church of Entry into Jerusalem[7] every bit well as to its sacral role in religious rituals. Finally, the name of Vasily (Basil) the Blessed, who died during structure and was buried on-site, was fastened to the church at the beginning of the 17th century.[10]

Current Russian tradition accepts two circumstantial names of the church building: the official[10] "Church of Intercession on the Moat" (in full, the "Church of Intercession of Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat"), and the "Temple of Basil the Blessed". When these names are listed together[44] [101] the latter proper noun, being informal, is always mentioned 2d. The mutual Western translations "Cathedral of Basil the Blessed" and "Saint Basil's Cathedral" incorrectly bestow the status of cathedral on the church building of Basil, merely are nevertheless widely used even in academic literature.[10]

Sacral and social role [edit]

Miraculous find [edit]

On the day of its consecration the church building itself became part of Orthodox thaumaturgy. According to the legend, its "missing" ninth church (more than precisely a sanctuary) was "miraculously found" during a anniversary attended by Tsar Ivan IV, Metropolitan Makarius with the divine intervention of Saint Tikhon. Piskaryov's Chronist wrote in the 2nd quarter of the 17th century:

And the Tsar came to the dedication of the said church with Tsaritsa Nastasia and with Metropolitan Makarius and brought the icon of St Nicholas the Wonderworker that came from Vyatka. And they began to offering a prayer service with sanctified water. And the Tsar touched the base with his own easily. And the builders saw that another sanctuary appeared, and told the Tsar. And the Tsar, and Metropolitan, and all the clergy were surprised by the finding of another sanctuary. And the Tsar ordered it to be dedicated to Nicholas ...

Allegory of Jerusalem [edit]

Palm Lord's day procession (Dutch impress, 17th century).

Construction of wrap-effectually ground-floor arcades in the 1680s visually united the nine churches of the original cathedral into a single edifice.[seven] Earlier, the clergy and the public perceived it as nine distinct churches on a mutual base, a generalized allegory of the Orthodox Heavenly Urban center similar to fantastic cities of medieval miniatures.[7] [103] At a distance, separate churches towering over their base of operations resembled the towers and churches of a distant citadel rising in a higher place the defensive wall.[vii] The abstract allegory was reinforced by real-life religious rituals where the church played the role of the biblical Temple in Jerusalem:

The capital urban center, Moscow, is split into 3 parts; the first of them, called Kitai-gorod, is encircled with a solid thick wall. Information technology contains an extraordinary beautiful church building, all clad in shiny bright gems, chosen Jerusalem. Information technology is the destination of an annual Palm Sunday walk, when the G Prince[104] must atomic number 82 a donkey carrying the Patriarch, from the Church of Virgin Mary to the church building of Jerusalem which stands side by side to the citadel walls. Here is where the well-nigh illustrious princely, noble and merchant families alive. Hither is, also, the master muscovite market: the trading foursquare is congenital as a brick rectangle, with xx lanes on each side where the merchants have their shops and cellars ...

—Peter Petreius, History of the Great Duchy of Moscow, 1620[105]

Templum S. Trinitatis, etiam Hierusalem dicitur; advertizement quo Palmarum fest Patriarcha asino insidens a Caesare introducitur.

Temple of Holy Trinity, besides chosen Jerusalem, to where the tsar leads the Patriarch, sitting on a donkey, on the Palm Vacation.—Legend of Peter's map of Moscow, 1597, as reproduced in the Bleau Atlas[106]

The last donkey walk ( хождение на осляти ) took place in 1693.[107] Mikhail Petrovich Kudryavtsev noted that all cross processions of the flow began, every bit described by Petreius, from the Dormition Church, passed through St. Frol's (Saviour'southward) Gate and ended at Trinity Cathedral.[108] For these processions the Kremlin itself became an open up-air temple, properly oriented from its "narthex" (Cathedral Foursquare) in the west, through the "royal doors" (Saviour'south Gate), to the "sanctuary" (Trinity Cathedral) in the east.[108]

Urban hub [edit]

Tradition calls the Kremlin the center of Moscow, but the geometric center of the Garden Band, get-go established as the Skorodom defensive wall in the 1590s, lies exterior the Kremlin wall, coincident with the cathedral.[109] [54] Pyotr Goldenberg (1902–71), who popularized this notion in 1947, still regarded the Kremlin as the starting seed of Moscow's radial-concentric organisation,[110] despite Alexander Chayanov's earlier suggestion that the system was not strictly concentric at all.[109]

In the 1960s Gennady Mokeev (built-in 1932) formulated a different concept of the historical growth of Moscow.[111] According to Mokeev, medieval Moscow, constrained by the natural boundaries of the Moskva and Neglinnaya Rivers, grew primarily in a due north-easterly direction into the posad of Kitai-gorod and beyond. The principal road connecting the Kremlin to Kitai-gorod passed through St. Frol's (Saviour's) Gate and immediately afterwards fanned out into at least two radial streets (nowadays-day Ilyinka and Varvarka), forming the cardinal market foursquare.[112] In the 14th century the urban center was largely contained within two balancing halves, Kremlin and Kitai-gorod, separated past a marketplace, simply past the end of the century information technology extended farther along the north-eastern axis.[113] Two secondary hubs in the west and s spawned their own street networks, but their development lagged behind until the Time of Troubles.[114]

Tsar Ivan'southward determination to build the church next to St. Frol'due south Gate established the dominance of the eastern hub with a major vertical emphasis,[114] and inserted a pivot point betwixt the nearly equal Kremlin and Kitai-gorod into the in one case amorphous market.[115] The cathedral was the main church of the posad, and at the same time it was perceived equally a function of the Kremlin thrust into the posad, a personal messenger of the Tsar reaching the masses without the mediation of the boyars and clergy.[116] It was complemented by the nearby Lobnoye mesto, a rostrum for the Tsar'southward public announcements first mentioned in chronicles in 1547[67] and rebuilt in stone in 1597–1598.[67] Conrad Bussow, describing the triumph of Imitation Dmitriy I, wrote that on three June 1606 "a few thou men hastily assembled and followed the boyarin with [the impostor's] letter through the whole Moscow to the principal church they call Jerusalem that stands right next to the Kremlin gates, raised him on Lobnoye Mesto, chosen out for the Muscovites, read the letter and listened to the boyarin's oral explanation."[117]

Replicas [edit]

A scale model of Saint Basil's Cathedral has been congenital in Jalainur in Inner Mongolia, near Communist china's edge with Russia. The building houses a science museum.[118]

References [edit]

- ^ Popova, Natalia (12 July 2011). "St. Basil's: No Need to Invent Mysteries". Moscow, Russia: Ria Novosti. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ a b "List of federally protected landmarks". Ministry building of Culture. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ "Cathedral of the Protecting Veil of the Female parent of God". world wide web.SaintBasil.ru. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 8 Baronial 2013.

- ^ "Kremlin and Carmine Square, Moscow". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ "Cathedral of the Protection of Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat". Moscow Patriarchy. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ Brunov, p. 39

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j m l k n o p q r south t u v Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 402

- ^ A concise English history of the evolution of the church's names is provided in Shvidkovsky 2007 p. 126

- ^ Brunov, p. 100

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shvidkovsky 2007, p. 126

- ^ Shvidkovsky 2007, p. 140

- ^ a b c d e "Pokrovsky Cathedral (in Russian)" (in Russian). Country Historical Museum, official site. Archived from the original on xvi Feb 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ "Kremlin and Red Foursquare, Moscow (WHS card)". UNESCO. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ^ "St. Basil's Cathedral". Dotdash. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Московский Кремль: собор Покрова Пресвятой Богородицы на Рву (храм Василия Блаженного) / Организации / Патриархия.ru".

- ^ a b Kudryavtsev, p. 72

- ^ Brunov, p. 41

- ^ О Троице на Рву в Москве. Того же году повелением царя и государя и великого князя Ивана зачата делати церковь обетная, еже обещался во взятие Казанскоe: Троицу и Покров и семь приделов, еже именуются на Рву. А мастер был Барма со товарищи. – Full annotated text in "Piskaryov Chronicle, office iii" (in Russian). Full Collection of Russian Chronicles. 1978. , also cited by Kudryavtsev, p. 72.

- ^ a b c Shvidkovsky 2007, p. 139

- ^ a b c d Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 399

- ^ Perrie, pp. 96–97

- ^ Watkin, p. 103

- ^ Olsen, Brad. Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations. CCC publishing. p. 155.

- ^ RBTH, special to (12 July 2016). "8 facts about Russia's all-time-known church – St. Basil's Cathedral". Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Saint Basil'due south Cathedral, Moscow 2018 ✮ Church building on Red Square". MOSCOVERY.COM. half-dozen July 2016. Retrieved 19 Oct 2018.

- ^ List of federally protected buildings, cited above, names Postnik Yakovlev and Ivan Shiryay the builders of the new Kazan Kremlin, 1555–1568.

- ^ Brumfield, p. 94

- ^ a b c d Buseva-Davydova, p. 89

- ^ a b c d e Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 400

- ^ Artwork distorts perspective and placement of ii churches. In existent life, they are nearly 400 meters from each other and are separated by hills and a deep ravine.

- ^ Cracraft, Rowland p. 95

- ^ "Sobor Vasilia Blazhennogo – machete (Собор Василия Блаженного – зашифрованный образ погибшей мечети)" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 29 June 2006. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ Moffett et al. p. 162

- ^ Watkin, pp. 102–103

- ^ Brunov, pp. 71, 73, 75

- ^ Batalov, p. 16

- ^ Shvidkovsky 2007, p. 7

- ^ a b Shvidkovsky 2007, p. 6

- ^ Shvidkovsky 2007, pp. 128–129

- ^ Brunov, p. 62

- ^ Brunov, p. 44

- ^ Brunov, p. 125

- ^ a b c d e f Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 401

- ^ a b c d Brumfield, p. 95

- ^ Shvidkovsky 2007, p. 128: "regular, not to say "rationalist" plan."

- ^ Brumfield, p. 96

- ^ Brunov, p. 109

- ^ a b c d e Brumfield, p. 100

- ^ a b Brunon, pp. 53, 55

- ^ Brunov, p. 114

- ^ Underwood, Alice E.Chiliad. "V Wild Facts about St. Basil's Cathedral". Russian Life . Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Brunov, p. 43

- ^ a b Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 389

- ^ a b Kudryavtsev, p. 104

- ^ Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 267

- ^ Brunov, p. 45

- ^ a b Brunov, p. 47

- ^ a b Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 49

- ^ a b Shvidkovsky 2007, p. 129

- ^ Buseva-Davydova, p. 58

- ^ a b c d Kudryavtsev, p. 74

- ^ Kudryavtsev, pp. 72, 74

- ^ Brunov, pp. 65, 67

- ^ Brunov, p. 67

- ^ a b Buseva-Davudova, p. 29

- ^ a b Brunov, supplementary book, p. 121

- ^ a b c d Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 403

- ^ a b Brunov, supplementary volume, p. 123

- ^ a b c d Schenkov et al., p. 70

- ^ Schmidt, p. 146

- ^ The moat, fed with waters of the Neglinnaya River, was built in 1508–16 – Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 268

- ^ Schenkov et al., p. 57

- ^ Schenkov et al., p. 72

- ^ a b Schmidt, p. 130

- ^ a b c Schmidt, p. 1,32

- ^ Schmidt, p. 129

- ^ a b Schmidt, p. 149

- ^ Schenkov et al., pp. 181–183

- ^ a b c d Schenkov et al., p. 396

- ^ a b Schenkov et al., p. 359

- ^ a b c Schenkov et al., p. 361

- ^ Schenkov et al., p. 318

- ^ Schenkov et al., pp. 396–397

- ^ a b Schenkov et al., p. 397

- ^ a b Schenkov et al., p. 473

- ^ Colton, p. 111

- ^ Colton, p. 220

- ^ Akinsha et al., p. 121

- ^ Colton, p. 277

- ^ Colton, p. 269

- ^ "St. Basil's was returned to land list in the mid-1930s" – Colton, p. 269

- ^ Run into, for case, Arkady Mordvinov's entry for the second phase of Narkomtiazhprom contest (1936), with the church in place.

- ^ Colton, p. 837

- ^ Pokrovsky sobor (Покровский собор). Soviet Academy of Compages. 1941.

- ^ "Pridel Hrama Vasilia Blazhennogo otkryvaetsa posle restavratsii (Придел Храма Василия Блаженного открывается после реставрации)" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 25 September 2008.

- ^ https://world wide web.efe.com/efe/english language/life/minor-russian-church-from-st-basil-circuitous-re-opens-afterwards-renovations/50000263-3822413 Reopen for services

- ^ A "sobor" in Orthodox tradition is any pregnant church that is prepared to and allowed by the Patriarch to host Divine Liturgy delivered past a bishop or a college-level cleric. Information technology is not necessarily the seat of a bishop; seat of the bishop, strictly correlating to Catholic cathedral, is "kafedralny sobor".

- ^ Brunov, p. 113

- ^ a b c Names (patron saints) of the sanctuaries get-go with the primeval known consecration, as in: Brunov, supplemental tables, pp. 6–10

- ^ Presently before his death M Prince Vasily, father of Ivan, accepted tonsure of a monk under the name of Varlaam. Connection between this event and the Church of St. Varlaam has non been confirmed past hard evidence.

- ^ Komech, Pluzhnikov p. 398

- ^ И прииде царь на оклад той церкви с царицею Настасиею и с отцем богомольцем Макарием митропалитом. И принесоша образы чюдотворныя многия Николу чюдотворца, кой прииде с Вятки. И стали молебны совершати и воду святити. И первое основание сам царь касается своима руками. И разсмотриша мастеры, что лишней престол обретеся, и сказаша царю. И царь и митропалит, и весь сунклит царьской во удивление прииде о том, что обретеся лишней престол. И поволи царь ту быти престолу Николину... – "Piskaryov Chronicle, part 3" (in Russian). Full Collection of Russian Chronicles. 1978.

- ^ Shvidkovsky 2007, p. 128, provides a summary of studies of the ideology of the cathedral

- ^ The style of 1000 Prince of Moscow, used past Petreius, has been in disuse for about lxx years, replaced by the style of Tsar.

- ^ Эта столица Москва разделяется на три части, первая из них называется Китай-город и обнесена толстой и крепкой стеной. В этой части города находится чрезвычайно красивой постройки церковь, крытая светлыми блестящими камнями и называемая Иерусалимом. К этой церкви ежегодно, в Вербное Воскресенье, великий князь должен водить осла, на котором из крепости едет патриарх, от церкви Девы Марии до церкви Иерусалима, стоящей перед крепостью. Тут же живут самые знатные княжеские, дворянские и купеческие семейства... – Petreius, pp. 159–160. Petreius visited Moscow in 1601–1605 and described the urban center equally it existed before the Time of Troubles.

- ^ Komech, Pluzhnikov, graphic supplement.

- ^ Bushkovitch, p. 181

- ^ a b Kudryavtsev, p. 85

- ^ a b Kudryavtsev, p. 11

- ^ For a graphic introduction of Fifty. Thou. Tverskoy's concept of concentric Moscow (1950s), see Schmidt, p. 11 and related annotations.

- ^ A popular explanation of Mokeev'southward theory, in Russian: Mokeev, One thousand. Ya. (September 1969). "Moskva – pamyatnik drevnerusskogo gradostroitelstva (Москва – памятник древнерусского градостроительства)". Nauka i Zhizn.

- ^ Kudryavtsev, p. 14

- ^ Brunov, p. 31

- ^ a b Kudryavtsev, p. xv

- ^ Brunov, p. 37

- ^ Brunov, p. 49

- ^ ...спешно собралось несколько тысяч человек, проводили боярина с письмом через всю Москву до главной церкви, называемой Иерусалимом, что у самых кремлевских ворот, возвели его там на Лобное место, созвали жителей Москвы, огласили письмо Димитрия и выслушали устное обращение боярина – Conrad Bussow (1961). "Chronicon Moscovitum ab a. 1584 Advert ann. 1612" (in Russian).

- ^ Hessler, Peter (9 Feb 2016), "Invisible Bridges: Life Along the Chinese-Russian Border", The New Yorker

Sources [edit]

- Batalov, Andrey (1998). "O datirovke tserkvi useknovenia glavy Ioanna Predtechi five Dyakovo (О датировке церкви усекновения главы Иоанна Предтечи в Дьякове)" (PDF). Materialy I Issledovania. Muzei Moskovskogo Kremlya (Материалы и исследования. Музеи Московского Кремля) (in Russian). XI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011.

- Brumfield, William Craft (1997). Landmarks of Russian Architecture: A Photographic Survey. Routledge. ISBN978-ninety-5699-537-nine.

- Brunov, N. I. (1988). Hram Vasilia Blazhennogo v Moskve (Храм Василия Блаженного в Москве. Покровский собор) (in Russian). Iskusstvo.

- Buseva-Davydova, I. L. (2008). Kultura i iskusstvo 5 epohy peremen (Культура и искусство в эпоху перемен) (in Russian). Indrik. ISBN978-5-85759-439-1.

- Bushkovitch, Paul (2001). Peter the Peachy: the struggle for power, 1671–1725. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-80585-eight.

- Colton, Timothy J. (1998). Moscow: Governing the Socialist City. Harvard University. ISBN978-0-674-58749-half-dozen.

- Cracraft, James; Rowland, Daniel Bruce (2003). Architectures of Russian Identity: 1500 to the Nowadays. Cornell University Press. ISBN978-0-8014-8828-iii.

- Komech, Alexei I.; Pluzhnikov, V. I., eds. (1982). Pamyatniku arhitektury Moskvy. Kremlin, Kitai Gorod, tsentralnye ploschadi (Памятники архитектуры Москвы. Кремль, Китай-город, центральные площади) (in Russian). Iskusstvo.

- Kudryavtsev, Mikhail Petrovich (2008). Moskva – trety Rim (Москва – третий Рим) (in Russian). Troitsa. OCLC 291098358. (2nd edition; first edition: 1991)

- Moffett, Marian; Fazio, Michael; Wodehouse, Lawrence (2003). A world history of compages. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN978-0-07-141751-8.

- Perrie, Maureen (2002). The Image of Ivan the Terrible in Russian Folklore. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0-521-89100-4.

- Petreius, Peter (1997). History of the Dandy Duchy of Moscow (История о великом княжестве Московском) (in Russian). Rita Print, Moscow. ISBN978-5-89486-001-5. (Original book written in 1615 and printed in Leipzig, in German language language, in 1620; translated to Russian in 1847 by Mikhail Shemyakin).

- Shchenkov, Alexei S.; Andrej Leonidovic, Batalov, eds. (2002). Pamyatniki arhitektury v dorevolutsionnoy Rossii (Памятники архитектуры в дореволюционной России) (in Russian). Moscow: Terra. ISBN978-5-275-00664-3.

- Schmidt, Albert J. (1989). The architecture and planning of classical Moscow: a cultural history. Diane Publishing. ISBN978-0-87169-181-i.

- Shvidkovsky, D. Southward. (2007). Russian architecture and the Westward. Yale University Press. ISBN978-0-300-10912-2.

- Watkin, David (2005). History of Western architecture. Laurence Rex Publishing. ISBN978-ane-85669-459-9.

External links [edit]

- Official website

- State Historical Museums home page

- https://instagram.com/saint_basils_cathedral/

- VLOG: St Basil'due south Cathedral Light Show

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Basil%27s_Cathedral

Posted by: healeycoled1948.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Time Is Service South West Church"

Post a Comment